Including: Tevila for First-Time Use, Bakasha & Public Tehillim on Shabbos,

March, 2023

Compiling a list of popular halachic myths would compromise more than one full column, but a few examples will prove helpful.

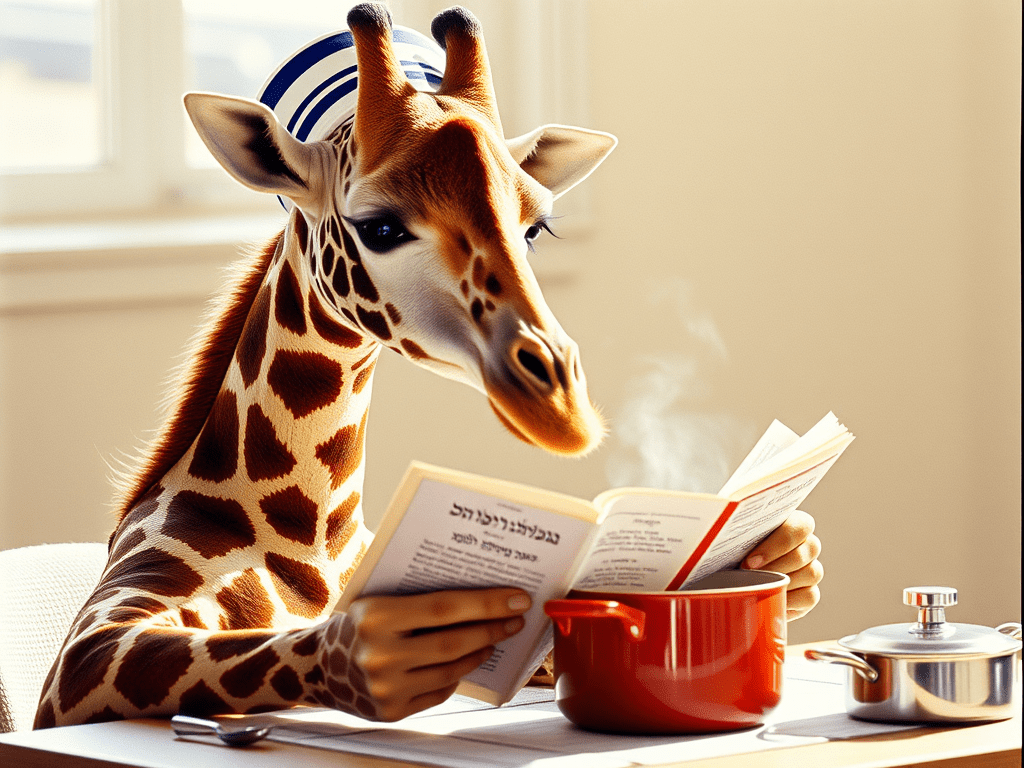

Although giraffes have simanei kashrus, kosher signs, we don’t eat them because we don’t know where on the neck to shecht it.

Although certain utensils require tevilah, one may use them the first time without toiveling them.

Both statements are false.

A giraffe’s long neck would make shechitah easier, not harder! How did this ficticious halachic rumor come about? Well, the real reason we don’t eat this mammal is because we generally avoid eating any land or air creature that does not have a tradition of being eaten by Jews. (This is aside from the impracticality of its consumption due to their expense and difficulty of finding and raising them.)

Among many concerns, without a mesorah, we may not be aware of issues that are unique to the animal in question, such as whether it should be classified as a chayah or beheimah, how to treiber (devein) it, how to deal with its forbidden fats, and whether certain signs of diseases render it treif.

A rav who is asked this question may explain succinctly, “We simply wouldn’t know how to shecht it.” Hearing this, one may incorrectly assume that the rav is referring to the animal’s most notable feature—its neck.

As for tevilah, whether it’s a vessel’s first use or its 465th, the halachah is the same -tevilah is required before use. I understand how this myth is perpetuated because I once saw it develop in real time. I was once explaining during a shiur that disposable pans do not require tevilah as long as they will only be used once, and an attendee commented, “Do you mean to say that first-time use never requires tevilah?”

No! But now understood where the confusion comes from. There are a number of factors that warrant tevilah; the utensil must be one that will be used directly with ready-to-eat food, and it must be made out of certain materials, etc. But first and foremost, it must be classified as a kli, a vessel, something of significance. Many poskim therefore posit that a flimsy item that is intended for one-time use is not a kli to begin with and hence would not require tevilah. (Some poskim even allow these disposables to be used two or three times before requiring tevilah.)

This is as opposed to a fancy, expensive dish, which is automatically considered a kli. In any event, it is easy to mistake the “one-time” halachah for the “first-time” myth.

Another common halachic myth that is much more nuanced is connected to the subject of war, which we have been discussing these past few weeks.

If asked why we don’t daven the regular Shemoneh Esrei on Shabbos, many would respond, “Because we are not allowed to make personal requests on Shabbos.”

But this is not the reason Chazal give (cf. Yerushalmi, Shabbos, 15:3 and Brachos, 5:2). Nor is it so simple that bakashos are generally not allowed on Shabbos; after all, we say Sim Shalom, Yekum Purkan, and the Yehi Ratzon for cholim—not to mention bentching and many other tefillos that remain unchanged on Shabbos. Consider as well Birchas Hachodesh, which is only said on Shabbos and is full of personal requests!

The background for these halachos is fascinating, and it relates directly to the way we should respond to an eis tzarah on Shabbos and as a kehillah.

The Gemara states that the reason we shorten the Shemoneh Esrei from 19 brachos during the week to seven on Shabbos is in order not to burden people (Brachos, 21a). Although the intention seems to be that Chazal wanted to shorten davening, it is clear from the rest of our Shabbos liturgy and leining that this is not the case.

Instead, the poskim explain that Chazal were referring to emotional tirchah. Our prayers, when recited with conviction, should awaken painful realities, and on Shabbos we are given a break from some of them (see Tanchuma, beginning of Vayeira, and Sefer Hamanhig, Shabbos, siman 11).

Knowing this is not simply academic Torah l’shmah but also affects halachah. For example, if one accidentally says even the first word of a weekday Shemoneh Esrei blessing on Shabbos (for example, “Atah Chonein” or “Refa’einu”), he must finish that brachah and then return to the Shabbos Shemoneh Esrei (Shulchan Aruch, siman 268; this is true even if he realizes his error before uttering Hashem’s name). The reason for this is precisely due to the fact that one is technically allowed on Shabbos to make a bakashah that he recites consistently.

However, it is true that Chazal also say that we must avoid certain types of bakashos on Shabbos (e.g., Bava Basra, 91a). Clearly, the prayers that were composed just for Shabbos—such as the Yehi Ratzon after candle-lighting and Birchas Hachodesh—and those for Yomim Tovim that happen to fall on Shabbos, such as Rosh Hashanah, are allowed (see Shulchan Aruch Harav, siman 288:8; shu”t B’tzeil Hachamah, 5:41; Bnei Yissas’char, Shevat 2:2; and Magen Avraham, siman 128:70). Last week we mentioned a view that even allows Avinu Malkeinu to be said when Yom Kippur falls on Shabbos.

What emerges from all of this is that daily tefillos may be recited on Shabbos, except for the middle blessings of Shemoneh Esrei. All other constant prayers, such as Elokai Netzor, may be recited. Special tefillos, even if they are bakashos, may also be said, especially those such as Yekum Purkan and Mi Shebeirach, which many see as a brachah and not a tefillah (Ohr Zarua, 2:89, and Shulchan Aruch Harav, siman 284:14). All other unique personal tefillos should not be said (Shulchan Aruch, 288:9).

However, if there is a sakanah, even for one choleh, one may daven for that person on Shabbos as long as he does not do so in a public way (ibid. 8, with Acharonim; see also Piskei Teshuvos, p. 489).

Now we arrive at our main question. May a shul hold a public Tehillim recitation for the current crisis? On the one hand, it’s sakanas nefashos, but on the other hand, although unique prayers are allowed in a dangerous and time-sensitive situation, doing so with others in a public way is not.

The Steipler ruled that when Eretz Yisrael is at war, Tehillim should be recited just as on a weekday (Orchos Rabbeinu Vol. I, p. 124). Some have said that during World War II, the special Yehi Ratzons and Acheinu that are recited on Mondays and Thursdays were said publicly on Shabbos after leining (shu”t Tiferes Adam 3:18).

A few weeks ago, a friend sent a group an email with a list of the hostages, asking that each person he sent it to take one hostage’s name and dedicate a perek of Tehillim to that person. He ended, “Chazal share that when one saves a life, it is as if he has saved the world (Sanhedrin 37a).”

This is certainly true, and has practical application when it comes to a physical act of salvation. However, obviously, we would not be allowed to be michallel Shabbos so as to purchase a Tehillim from which to daven!

Rather, when it comes to divrei ruchniyus and tefillah, we must yield to the Torah and halachah and allow Hashem to do the rest.

May Hashem accept our tefillos, save us from michshol, and enable us to defer, always, to halachah. ●

Leave a comment