November, 2018

For many of us, the thought of prison may evoke images of Rav Aryeh Levin, z”l, walking through the halls of Jerusalem’s original slum-hole jails, or perhaps the various dapei haShas where Chazal discuss the process of incarceration.

However, most of us go through life with only the most abstract, even caricatured, mental picture of what the “inside” of a prison is like.

I am not so lucky.

Years ago I spent time in prison.

No, not as an inmate, but as a clergyman. For a very short period of time, I worked as a chaplain for the New York State Department of Corrections.

On the surface it sounds like a good job. When you work for the state, health care and retirement benefits are fantastic, you get overtime pay, and there are other perks as well.

But, alas, you have to work in prison.

I was a rav in Buffalo at the time, and what with my family, shul, the vaad and a myriad of other activities, I barely had time for this add-on. But after a meeting in Albany in the summer of 2007, I said I would give it a try.

It was the most depressing job I have ever experienced. I visited one of two prisons once a week, from nine in the morning until five at night. I drove an hour each way, arriving exhausted. After my security check, they would wave me in and I would hear the crash of the bars closing behind me. Imagine working each day in a place where bars lock you in, as if the boss were saying, “For the next eight hours you ain’t goin’ anywhere!”

When five p.m. arrived, the prison doors opened to let me out—and let me tell you, it actually felt like my sentence was over, as though I were finally free. I always had an impulse to rush to my car in case they suddenly decided to extend my sentence.

I have many stories from my time in the prison, but here I would like to share just one.

A few weeks ago I wrote a series of articles in this space about the halachos and minhagim surrounding the painful issue of a fallen or destroyed sefer Torah. I received more correspondence about those articles than about any other topic I have covered thus far.

A few weeks ago I was at an event where someone approached me and said, “Boy, those were some depressing articles.”

I became defensive. “What do you mean?” I asked.

He explained that every story I had told and every halachah I had mentioned involved a horrible case of a sefer Torah leading to tragedy.

Suddenly, I had a flashback.

“Well, to make up for that, let me share with you a story about a sefer Torah protecting us, and not just about our trying to protect a sefer Torah.”

And I shared with him the following prison story.

On my first day on the job, I was not shown my office; instead, it was pointed out. You see, it was a ten-minute walk from the gates to the building that housed the chaplains’ offices.

I naively pondered aloud which one of the officers would be escorting me through the yard (filled with inmates) to the building.

The guards looked at me with pity, then laughed. “Rabbi, we are all on our own here. You should be fine.”

“Should”?!

I made my way apprehensively along the path, glancing continuously at the watchtowers, as if summoning the guards up there to pay attention to this lone man with the yarmulke making his away through groups of inmates.

They had announced my arrival on the P.A. system so as to give all the Jewish inmates time to come meet me in that building. I was to spend the first half of my day there giving a class, and the second half meeting with prisoners who had made appointments. There were no frum inmates in this prison, but we knew of fifteen who identified as Jewish.

I do not recall if I was relieved or disappointed when I entered the building only to discover that the lights were off and not a single person was waiting to hear my shiur.

I slowly explored the office area and found a door that said “Chaplain” on it. It was dark, I was still antsy, and I was desperate to turn on some lights.

As soon as I hit the switch, as if out of nowhere, I saw him.

If memory serves me, he must have been about six foot six and perhaps 45 years old. I certainly remember his tattoos. He was large and looked mean.

Here I was, alone in a prison building, with this inmate in front of me.

“Are you that rabbi they announced this morning?”

I figured that if he planned on killing me, it might as well be al kiddush Hashem, so I said, “Yes, I am the rabbi.”

I tried to put up a brave front, but my legs were buckling. I was thinking that I should have listened to my wife, who had not wanted me to come work here.

“Okay, Rabbi,” he began. “My name is J.J., but you can call me Yaakov Yosef.”

It was the only time in my life that I experienced a strange combination of extreme relief and intense confusion all at once.

I asked him to take a seat, and I sat down at the desk. I waited a bit before asking him some questions. He likely thought that I was gathering my words, but I was really still catching my breath.

“J.J.—Yaakov Yosef—are you religious?”

“No,” he said. He told me that he had never been religious, had never gone to Hebrew school or had a bar mitzvah.

“I don’t understand. I have a list of fifteen Jewish inmates. This prison has not had a chaplain for a while, and you are the only one who shows up to study?”

He looked at me quizzically. “Well, rabbi, I may not be a good Jew, but I want to be one some day.”

He went on to share with me the story of his life and how he had wound up in prison. Suffice it to say that he had earned his place there (as did everyone I met that year. No one ever claimed—to me, at least—that they were innocent of their crimes; indeed, they were all too happy to share their often heinous criminal histories.)

After he had told me his awful life story, I could not help but ask, “But if you had no Jewish upbringing, how is it that you still care? How is it that you still remember your Jewish name?”

After five years in Buffalo, I had been involved in several divorces where the husband—even though he claimed to be “traditional”—had no idea what his Hebrew name was. Sometimes these men would stop the proceedings to call their mothers!

In any event, Yaakov Yosef explained. “I grew up in Flatbush. The only one in my family who cared about his Judaism even a little was my mother’s father. But even he only went to shul once a year, on Rosh Hashanah. One year he decided to take me along. I must have been six or seven years old at the time.

“I had never been to shul before—or much after—so I clearly remember it. We walked in when they were taking the…the…”

“Torah?” I suggested.

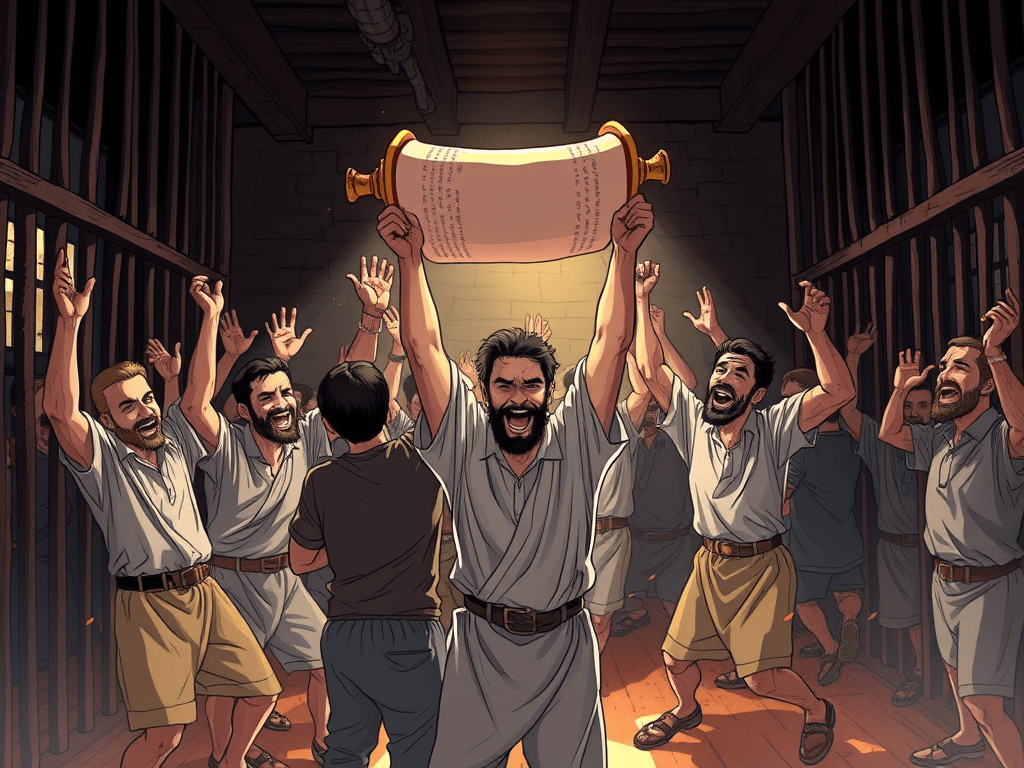

“Yes, the Torah. They were taking it out of the ark. All of a sudden I saw these old-timers with their grandchildren on their shoulders, or in their arms, running up to the Torah. The children all watched as their grandfathers lovingly kissed the Torah, and then they did the same. The joy on their faces was pure; they were happy.

“Throughout my years in gangs and crime, I thought about that visit to shul all the time. I promised myself that if this nation could love the Torah that much, then I would never forget that I am a Jew, and I would never forget that my real name is Yaakov Yosef.

“And that, Rabbi, is why I showed up today.”

I shared this story (and another amazing sefer Torah story, for another time) with this guest at the event.

“Okay,” he said. “That is a less depressing sefer Torah story. Just promise you will put it in your next column…”

Leave a comment